FLIR and WWF Join in Search for the Masked Bandits of the Prairie

Teledyne FLIR has once again partnered with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in its mission to protect vulnerable wildlife and restore struggling habitats. The organizations met in central Montana at the Fort Belknap Reservation to track black-footed ferrets, one of North America’s most endangered mammals. The goal was to test infrared camera solutions, both as a fixed-mount camera and as a drone payload, to determine if the technology could provide a faster, more accurate method of spotting the elusive ferrets. Ultimately, WWF aims to not only support the repopulation of this endangered species, but to also support the A'aninin and Nakoda tribes living on the reservation in returning their animal relative to its native home.

Searching For Black Footed Ferrets

Teledyne FLIR and the WWF join together in search for this masked bandit.

Fort Belknap is part of the Northern Great Plains, which encompass more than 180 million acres across five U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. Covered by prairie grass and farm fields, blown by high winds, this vast expanse is home to the tiny, elusive black-footed ferret and its prey, the prairie dog. Black-footed ferrets once numbered in the hundreds of thousands across the prairie but fell to just a few dozen in the last century and were declared extinct in 1979. It wasn’t until a residual wild population was discovered in Wyoming in 1981 that United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) could begin a captive-breeding program to bring the ferret back from extinction.

The Fort Belknap Fish and Wildlife Department (FWD) first reintroduced black-footed ferrets to the reservation in 1997 yet initial efforts failed due to an outbreak of sylvatic plague – a non-native disease lethal to the species. With plague mitigation tools in hand, they reintroduced ferrets again 2013 and have since focused on keeping the current population healthy enough to reproduce. With assistance from the WWF and USFWS, the FWD is trying to reach a minimum of 30 breeding adult ferrets; as of 2022, they were on track with 16 adults and 32 ferrets total. There is still much work to be done, though, as the USFWS hopes to eventually have 3000 adults nationally compared to the current wild population of 300.

The black-footed ferrets’ decline can be traced back to plague introduced to their habitat, European settlers plowing grassy plains, and government-sponsored poisoning of the ferrets’ prey—prairie dogs— which compete for the same grass needed to feed sheep and cattle.

“Plague, plowing, and prairie dogs; these are the “3 P’s” responsible for the ferrets dwindling numbers,” says WWF’s Black-footed Ferret Restoration Manager, Kristy Bly. “You’ve got a species whose loss was directly tied to human activity, so we have a moral and biological obligation to return what still can be,” she explained during the recent trip to Fort Belknap.

The largest threat to the already dwindling species today is sylvatic plauge, as ferrets are highly susceptible to it. Plague is a bacteria carried by fleas who then infect ferrets and prairie dogs. It’s for these reasons that disease mitigation and vaccinations are the highest priority for the WWF and others in ferret restoration.

Black-footed ferret returning to its burrow.

As you might imagine, capturing and administering vaccinations to an elusive, nocturnal animal has its challenges. Biologists are literally in the dark when it comes to locating the ferrets when they’re hunting at night. Biologists currently use a truck-mounted spotlight to sweep across areas known to have prairie dog populations and look for the ferret’s iconic emerald-green shine from their eyes.

Once they’ve located a ferret, they head to the area to set up traps in what they hope are ferret burrows. Then, they set off to sweep for another ferret while waiting for the trap to spring.

A burrow trap used to capture ferrets.

The spotlight solution is limited, as it’s entirely dependent on having a line of sight with the ferret. If a ferret isn’t looking at the light or if any terrain gets in the way, there won’t be any shine to identify them. This is where the WWF and FLIR hoped technology could provide a solution.

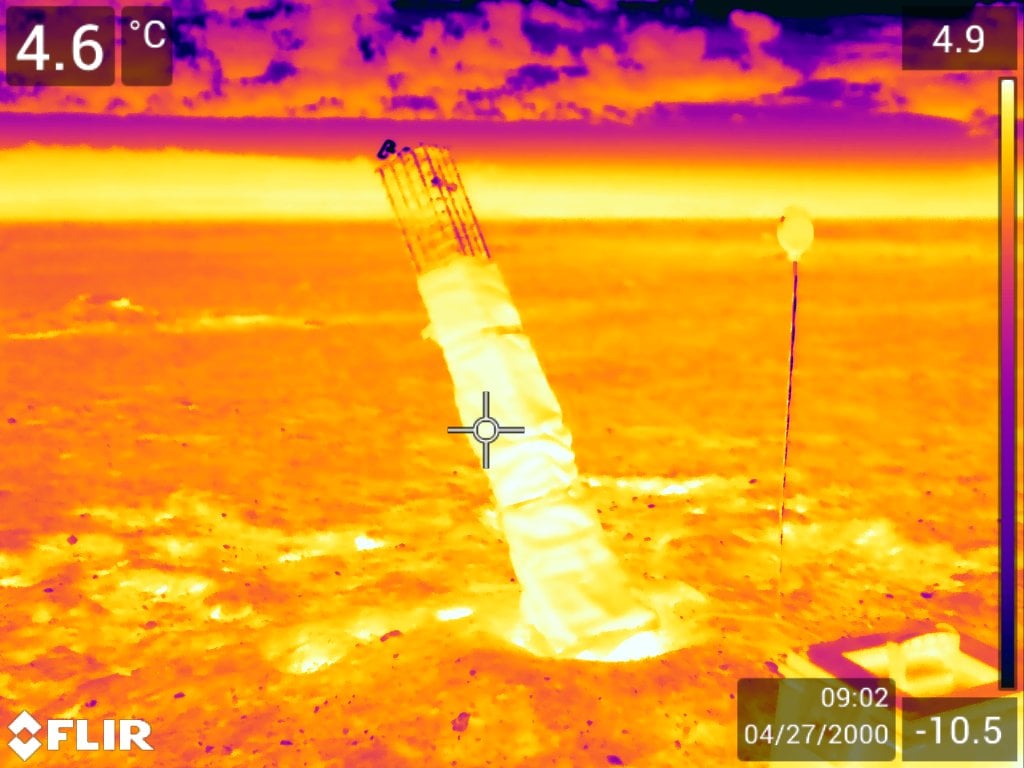

The WWF worked with Teledyne FLIR to test a tower-mounted Tau 2 OEM thermal imaging camera with a 100 mm lens, encased in a pan-tilt unit, as well as a drone equipped with a thermal imaging camera. Thermography expert, Shawn Jepson, used the tower camera to search for signs of heat across the prairie—hoping to determine whether the camera could distinguish between heat emanating from underground burrows and the heat of a moving ferret. Meanwhile, Jesse Boulerice of Steller’s Jay Solutions swept the area with the drone to detect movement that might indicate a ferret.

Tower mounted thermal camera.

The tower camera can provide significant clarity at 200 meters, making the search in wide areas much easier and potentially useful for counting the number of individual ferrets in a liter. The WWF and Boulerice hoped the drone could provide confirmation of ferrets when they were too far away from the tower.

While testing the tower on their second night, the group saw success: they located a ferret within the first ten minutes and three ferrets total in one night. As Jepson picked up a heat signature through the tower camera, he relayed the information to Boulerice, who flew the drone over the area to verify what they saw. Once a ferret was confirmed, biologists quickly set a trap in its burrow with a radio box that would signal when the ferret emerged into the trap.

With the ferret trapped, a biologist could retrieve the ferret and take it to a mobile lab with the equipment for administering anesthesia, performing vaccinations, and inserting a tracking chip for ferrets that had never been caught or tracked before. Once the ferrets recover, they’re carefully placed back in their burrow.

Ferret sedated before receiving vaccination.

Ferret being returned to its burrow.

In terms of efficiency, the use of pan-tilt and drone-mounted thermal cameras could provide massive benefit for time and energy. “There’s always the potential that you go out and set things up and nothing happens but that hasn’t been the case tonight,” says Boulerice. “I think the future is stations like this with efficient ways of relaying to the people in the trucks where those ferrets actually are. I think tonight has shown that it has a lot of potential.”

Fort Belknap holds one of just 14 ferret populations in North America and is the first ferret restoration lead by a native nation. The restoration of an endangered species is important by itself, but it brings even more meaning to the local native American population. Bly told FLIR of Lyle Pearlman, one of the elders on the reservation, whose grandfather would adorn himself in ferret pelts for important events and his eventual burial.

“We hope to advance black-footed ferret recovery and bring them back to their rightful place within the prairie ecosystem, and also help bolster the relationships native people have with their lands and animal relatives,” Bly said. “What is more rewarding than helping others achieve a vision that is so critical to restoring the endangered masked bandit of the prairie? It’s an incredible honor to work with the tribes of Fort Belknap.”